By Ahmed Usman

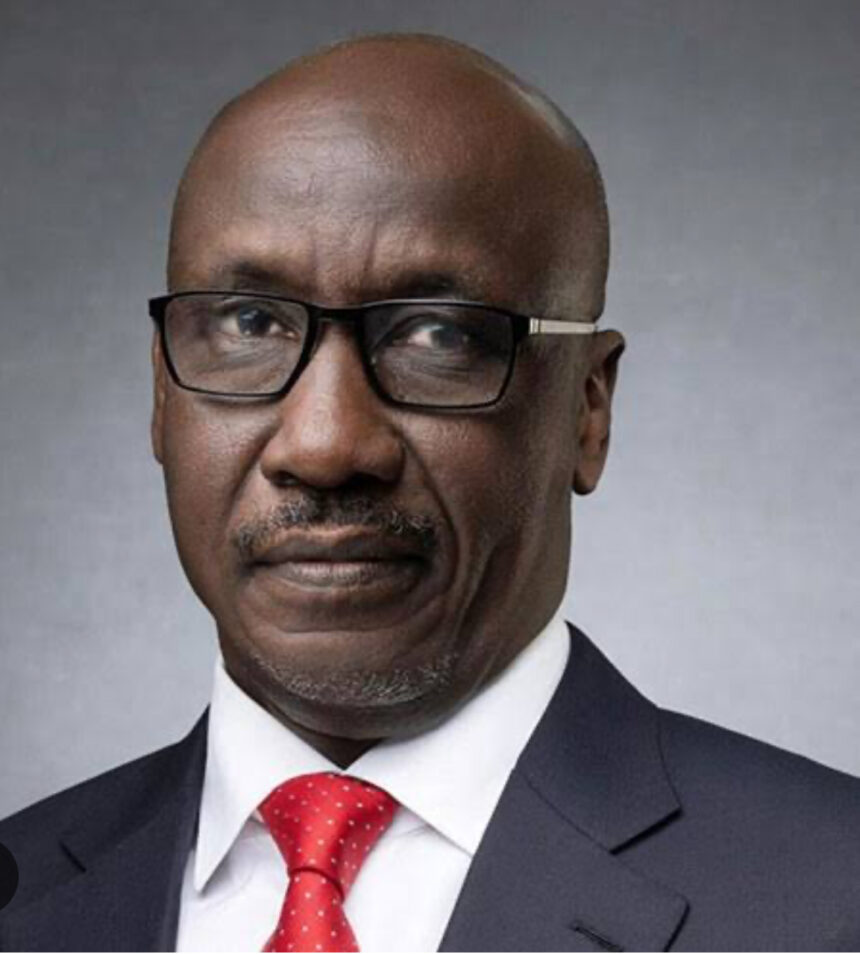

They never see it coming, the fall. One minute, they’re draped in the silk of state power, voices thundering across boardrooms and briefings; the next, they are footnotes in their own tragedies. Mele Kyari, once the oil czar of Africa’s largest crude producer, now drifts in the dusk of disgrace. He has been abandoned, and left in the lurch, like the proverbial glutton, who stayed too long at the banquet of ephemeral power.

He should have known better. Power in Nigeria does not whisper its expiry, it simply vanishes. It does not ask you to leave, it unseats you mid-sentence, mid-scheme, mid-plea. And so it was that Mele Kyari, the once-untouchable boss of NNPCL, found himself clutching at shadows, making phone calls that rang out unanswered, trading dignity for delay. He could have bowed out at 60, garlanded with grace. Instead, he chose to linger, and got booted out. Mele Kyari’s exit wasn’t merely a removal, but an unmasking: of sabotage, ego, and a man whose time had passed, but mistook silence for consent and proximity for privilege.

Kyari, once the oil emperor of the Nigerian oil sector, presided over the nation’s petroleum fortunes with imperious arrogance. But today, he walks alone. No phone calls. No door left ajar. Only silence and scorn greet the former Group Chief Executive Officer of the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL). Like Godwin Emefiele before him, Kyari has joined the infamous club of once-powerful men who couldn’t read the room, and quit when the drums still roared. Now he finds himself clutching at faded glory.

However, his descent wasn’t sudden. It was an inevitable, tragic rendition of hubris; crafted in the mold of Nigeria’s sit-tight bureaucrats who confuse high office for immortality. His was a slow, humiliating collapse, marked by pleading phone calls, desperate meetings, backdoor alliances, and ultimately, a final sacking that stripped him not only of power, but of dignity.

Mele Kyari had the opportunity to leave the stage when the ovation was at its peak, or at the very least, at tolerable decibels. Instead, he clung to the trappings of his position like a man afraid to live without air. At the dawn of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s administration, Kyari reportedly begged to be spared the sack. His appeal was laden with sentiment: he would be turning 60 in January 2025 and wished to retire honourably with that milestone.

The president, sympathetic but cautious, let him linger. But instead of exiting gracefully once the birthday candles were snuffed out, Kyari began to sprint—begging, lobbying, crawling through the corridors of influence, seeking help from political titans to retain the job his time had clearly expired on. He turned 60, but wouldn’t go. He made calls, pulled strings, whispered promises of reform, and painted ghostly images of a petroleum utopia he could still usher in—if only given more time. But time, like power, runs out.

A Systematic Failure with National Consequences

Under Kyari’s stewardship, the NNPCL became a theatre of missed opportunities, corruption whispers, and mismanagement. The country’s oil production floundered. Subsidy regimes lacked transparency. Refinery revivals became bottomless pits for public funds. And the cost of petrol—despite his touted reforms—soared, throttling a weary nation already buckling under inflation.

Where there should have been foresight, there was fumbling. Where leadership was demanded, there was only lethargy. The NNPCL’s opacity deepened. Contracts vanished into black holes. Accountability became a relic of the past.

The ordinary Nigerian, forced to spend nearly half of daily earnings on fuel, was the most wounded. Kyari’s tenure was a pyre of hope for millions who expected liberation from the old order. Instead, they got a repackaged chaos—with new faces but the same tired script.

Those close to the saga recount how, in the weeks leading to his eventual ouster on April 2, 2025, Mele Kyari scurried like a man possessed. He called favours owed, showed up uninvited at powerful gatherings, and groveled before power brokers who once dined at his table. His pleas were simple: save me.

But it was too late. Even before the announcement was made, his allies had begun to thin out. The new sheriff at NNPCL, Bayo Ojulari, had stepped in with quiet authority and laser focus. Kyari’s loyalists in the system—Bala Wunti of NAPIMS, Lawal Sade, and Ibrahim Onoja of Kaduna Refinery—were shown the door in a sweeping restructuring that felt both cleansing and cathartic.

Over 200 staff were affected. Women emerged in new leadership roles. Maryam Idrisu and Obioma Abangwu now stand where once the Kyari loyalists held sway. And within NNPCL’s glass towers, there’s a new language: performance, transparency, merit.

The Dangote Betrayal: Sabotaging National Good for Personal Empire

Perhaps the darkest shadow on Kyari’s legacy was his bitter antagonism toward Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote, and the now-iconic Dangote Refinery. In a twist of bitter irony, what should have been a moment of national pride—the crashing of fuel prices by a homegrown, $20 billion refinery—became an orchestrated nightmare.

When Dangote’s refinery crashed the price of petrol to N860 per litre in Lagos and even lower in some regions, it brought a wave of economic relief. Inflation slightly dipped. The cost of food and manufactured goods followed. Nigerians, after months of suffering, caught a breath of fresh air.

But behind the scenes, Kyari’s NNPCL was seething. Rather than welcome the refinery’s positive disruption, they moved swiftly to end the naira-for-crude swap deal that allowed Dangote access to locally-sourced crude oil. The message was cruel and calculated: if you can’t sell fuel at our inflated prices, we’ll strangle your crude supply.

Kyari’s NNPCL demanded payment in US dollars—knowing full well that Dangote was selling refined products in naira. It was a manufactured mismatch designed to break the refinery’s wings.

Within days, the gains were reversed. Petrol prices shot back to N970 in Lagos, and crossed N1,000 in the North. Dangote had to halt price crashes. Once again, the ordinary Nigerian bore the brunt of a mafia’s greed and a former GCEO’s personal vendetta.

The Oil Mafia, Tinubu’s Dilemma, and a Country Held Hostage

Sources close to the presidency confirm what many suspect: the petrol importation mafia—with dollar-drenched fingers—was behind Kyari’s last-minute attempts to destabilise the Dangote Refinery. Their profits were melting with each price cut. Dangote’s success was their death knell. Kyari became their tool—a willing puppet in their mission to maintain the fuel importation racket.

Even after Tinubu publicly touted refinery revival and fuel subsidy removal, the same government—through Kyari’s NNPCL—was still issuing import licenses and draining over N5.5 trillion between October 2024 and January 2025 alone.

How does a country destroy its own solutions to keep foreign merchants smiling? Why empower a mafia while stifling indigenous industrialists?

Left in the lurch

Today, Mele Kyari is learning the harshest lesson of power: its loyalty is paper-thin. All the men and women who once buzzed his phones for favours have disappeared. Those who sang his praises are now sharing whispered allegations. Some, sources say, are even actively feeding anti-graft agencies with material for his prosecution.

Like Emefiele, Mele is now the one chasing. He calls. He begs. He wants protection from the storm he helped brew. But Abuja, ever fickle, has moved on.

There are already murmurs of multi-billion naira investigations into crude deals, opaque trading arrangements, and shady subsidy books. The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) is circling. Kyari’s name, once written in marble, is now penciled in on corruption lists.

And as his isolation grows, so too does the bitterness. One source described him as “angry, betrayed, and disillusioned.” Another said he’s been “shocked at how quickly his empire collapsed.”

The Final Lesson: Quit, or Be Dragged Out

Mele Kyari could have left on his own terms. He could have walked into the sunset with honour and applause. But like so many Nigerian public officers before him, he believed the myth of permanence. He mistook influence for invincibility.

Like Emefiele, he stayed too long. And now, like Emefiele, he will be probed, isolated, and humiliated. Their stories are cautionary tales in hubris, tales that warn every public servant: power is rented, never owned.

And when your lease is up, it’s better to hand back the keys than be thrown out with your name smeared and your legacy shredded.

Mele Kyari’s fall is not just a personal tragedy, it is a national parable. It reminds us, that reform cannot thrive where selfishness resides, that legacy cannot blossom where ego reigns. And that power, no matter how vast, is a shadow that’s transient.

Mele was one wicked individual whose interest is self over the masses.

Mele kyaei made the negotiation of PMS and other petroleum product to be as high as what it is.

The price we areanagung to pay is not the best we could get . Mele made it so , be ause if dangite had gone down to about 400 Naira, it would have exposed as it has exposed the greed in their sporit